RELATED: ‘It took my breath away,’ Memphis Belle unveiled at AF museum

Once numbering 16.1 million in uniform, as of 2016 the U.S. Census Bureau estimates fewer than 770,000 World War II veterans across the nation survive with about 33,000 of those living in Ohio.

On Memorial Day, these are a few of their stories.

These Miami Valley veterans — and one wartime civil service worker — share a common bond not only of service but as neighbors at One Lincoln Park in Kettering.

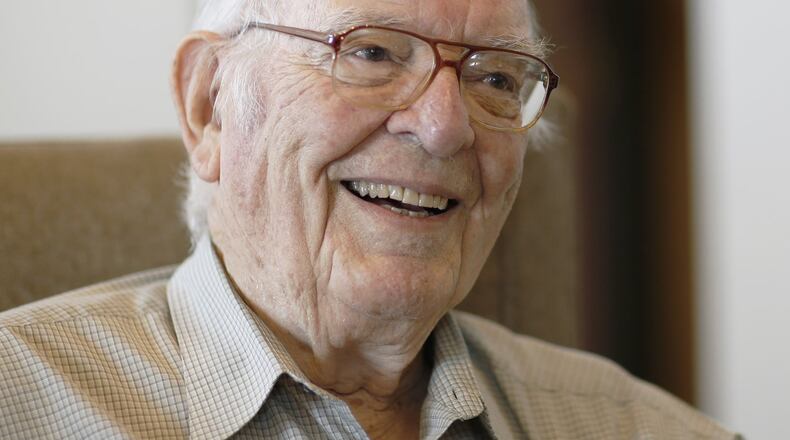

John M. Hood: Navy sailor

Surrounded by smoke, John M. Hood, 92, was in the middle of the Pacific aboard the destroyer USS Nicholson between an ammunition ship on one side and an oiler hoping a Japanese kamikaze attack didn’t strike.

Off the coast of the island of Okinawa, the electronics technician was part of the ongoing fight to take the Japanese island in 1945.

Boats laid down the smoke in the hope it would conceal ships from kamikaze attacks, swarming in explosive-laden planes in the skies targeting U.S. warships.

“We couldn’t see our hand in front of our face because it was covering the place with smoke,” he said.

A #WorldWarII #veteran remembers his servicehttps://t.co/n2Vlx04bFi #USNavy #PearlHarbor #MemorialDayWeekend #WWII

— Barrie Barber (@barriebarber) May 27, 2018

While Hood was handling five-inch projectiles on deck, a red alert sounded. ”The word went around us that the Japanese would come in and fly low and would fly into the smoke until they hit something.”

“It was pretty scary, it really was,” he said.

But the ship survived unscathed.

Many warships and sailors weren’t as lucky.

In another raid, Hood remembers sailing up to what was left of a destroyer after the Japanese attacked.

“There was nothing left of the destroyer except just a floating wreck,” he said. “… Looking over the side, you could actually see water right down through the middle of the ship.”

The Colorado native got aboard the ship at Pearl Harbor in the winter of 1945 and kept sailing throughout the war before he disembarked in Charleston, S.C.

Hood vividly recalls being on watch off the coast of Japan surrounded by hundreds of ships when the war ended with the dropping of the atomic bomb. U.S. warplanes bombed Hiroshima and days later Nagasaki in August 1945.

He and millions of troops had prepared for a possible invasion of Japan to end the war before the surrender.

“At the time, we were all very, very glad that we didn’t have to make that invasion because we would have lost approximately a million troops,” he said.

After the war, Hood, who married and had a family, was a Department of Defense research engineer and a college professor.

Russell Hastler: Night air warrior

Under moonlight skies, Russell “Cliff” Hastler flew in black B-24 bombers on secret missions to help the underground resistance in occupied Europe.

The Office of Strategic Services called on the Army Air Forces to fly the dangerous missions. His unit, the 801st/482nd Bombardment Group, were the forerunners to the U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command.

Known was the “Carpetbaggers,” the crews flew from Harrington Field, England, on missions to supply the French resistance and drop parachutists in preparation for D-Day, according to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

“We dropped spies and supplies,” said the 93-year-old Akron native, who was a gunner aboard the warplane and had left high school to join the war effort.

Hastler wanted to be a pilot, but the military had other plans.

“… They came along and said they had an excess of pilots, bombardiers and navigators and so they sent me to gunnery school,” he said.

Night flights in the B-24s would roam as far as Norway and Denmark, and the cover of darkness gave some sense of safety, but not an escape from danger.

“I guess we felt safer than the day guys because it was hard for them to send fighters up to intercept us,” he said. ”They couldn’t find us at night time.”

Even so, German fighter planes were a present threat.

“We’d fire ahead of them and they’d break off,” he said. “As soon as they saw the tracers coming over the front of their airplane, why they’d break off and leave us alone.”

The retired Air Force colonel, who served at Wright-Patterson, married and had a family. He attended a Congressional Gold Medal ceremony in March that recognized the World War II contribution of the OSS, forerunner of the CIA, and units like the Carpetbaggers.

Joan Weinland: Army mapmaker

Joan Weinland never served in uniform, but her work was vital to World War II efforts.

The Indianapolis native signed up with the Army Map Service, meticulously drawing lines on maps of the islands near Japan.

The Army had sought 100 high school students in Indianapolis to do the work, and Weinland, now 94, was among the few chosen. She trained for several months, selected because of her four years of art in high school.

RELATED: Five reasons the Memphis Belle exhibit is among the most impressive at the Air Force museum

“It was a very fascinating job, and every once in a while the (Army) Corps of Engineers officers would come in and tell us not to make mistakes” because of the importance of getting everything right for service members using the maps in the field.

“They always told us what could happen if we made mistakes. It was a very exacting job.”

She kept the purpose of her civil service work secret.

“My parents didn’t know,” she said. “Nobody knew.”

Weinland attended college after the war, married, raised a family, and lived in Maryland and Florida before moving to the Miami Valley.

Viola Nichols: Navy WAVES

They volunteered by the thousands for the Navy WAVES – or Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service —and Viola Nichols decided to join in New York City.

“I think it was on the spur of the moment,” the 99-year-old Nichols said. “I went by a recruiting office and the next thing I knew I was in.”

She was a dental assistant in the civilian world and would do the same job in uniform.

RELATED: New mission: Here’s how restorers spent decades saving the Memphis Belle legacy

“I liked it,” she said. “In fact, it was the best thing for me. It brought me out of my shell and I got a lot of benefits from it.”

The sailors who filed into the clinic did not talk about the war, she said.

Nichols lived in a dormitory with other WAVES at Hunter College when not working.

“Oh, heavens, there were a lot of them,” she said. “I think they filled two buildings.”

After the war, the New York native married, raised a family and worked as a dental hygienist.

James Leach: Army medic

James E. Leach was an Army medic with the infantry after he was drafted in 1942.

The 93-year-old Jackson County native who grew up near Chillicothe would see the war and the world in uniform.

Though memories have faded, Leach remembers arriving at a seaport in France and making his way to Czechoslovakia.

“I was with the infantry,” he said. “Wherever they went, you went with them.”

PHOTOS: Memphis Belle exhibit taking shape

He doesn’t recall the battles. “I don’t even try to think of them,” he said.

He was later shipped off to the Pacific Theater, he said.

“They dropped the (atomic) bomb while we were on the high seas and we went right into Tokyo Bay,” he said.

His unit took control of an airport, he said.

“I went through Tokyo and it was kind of tore up in spots,” he said.

“The main thing I can remember about that was how everybody was hungry … they seemed glad to see us because I think the public was pretty well starved because there was no food.”

He returned home in about a year, got married, raised a family and worked for GM, NCR and the Dayton Fire Department.

“I was glad (the war) was over, and I was still here, and I wasn’t hurt in any way,” he said.

MUST READ QUICK STORIES

Wright-Patt treating tainted water in contaminated wells

Military base water safety questions remain as fight for study continues

About the Author