The Great Flood of 1913 forever changed the landscape of Butler County in profound ways that can still be seen today.

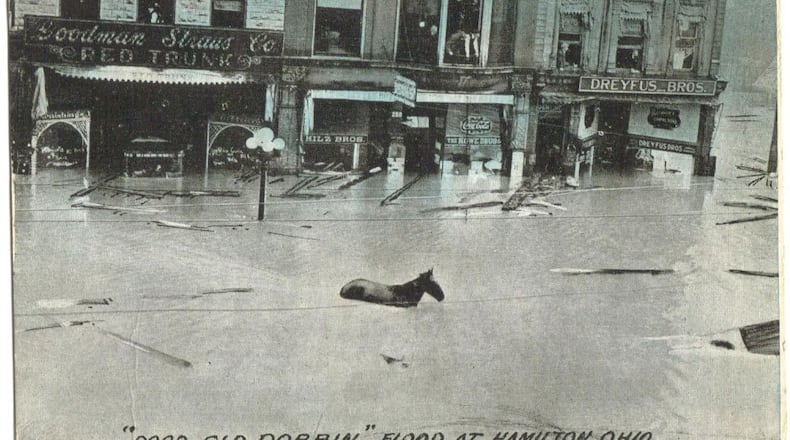

The rushing waters of the Great Miami River washed away bridges and houses all along its expanse, claiming hundreds of lives and destroying the canal system, covering more than four-fifths of Hamilton, mostly on the city’s lower-lying East Side.

From that disaster, however, came the largest public works project of the day, the Miami Conservancy District, which served as a model for similar plans throughout the country.

MORE AREA HISTORY: Here’s what life in Hamilton looked like through the years in black and white photos

“For many survivors of the 1913 flood,” writes local historian Jim Blount in his 2002 book “Butler County’s Greatest Weather Disaster — March 1913,” “… the emotional scars remained for a lifetime. Terrifying flood memories caused people to turn their backs on the flood.”

Indeed, it wasn’t until the last part of the century that the emotional wounds seemed healed enough for Hamilton — where an estimated 200 people died in the flood — to renew its relationship with the Great Miami River. With the construction of the low-level dam off Neilan Boulevard in the early 1980s, citizens once again began using the river for recreation, and city leaders now see Riverfront development as an integral part of Hamilton’s future.

Middletown is also looking at ways to reconnect with its river. Though the city didn’t experience the loss of life that Hamilton did, more than 1,000 Middletonians were displaced by the flood waters and dozens were injured. Sam Ashworth, of the Middletown Historical Society, credits the 1913 flood for renewing conversations that led to the construction of a local hospital four years later.

Storm of the millennium

The weather system that resulted in the Great Flood of 1913 was “the most wide-spread disaster in the history of the United States,” according to Trudy E. Bell, science writer author of half a dozen articles on the weather of 1913 and the Arcadia book “The Great Dayton Flood of 1913.”

All throughout the Midwest and even as far as the Hudson River in Troy, N.Y., the water that fell resulted in record water levels for dozens of rivers. Terra Haute, Ind., Omaha, Neb. and Council Bluffs, Iowa, are all commemorating what they refer to as “The Great Easter Tornadoes”, Bell said.

“For Ohio and Indiana, it was a one-two punch,” she said.

The region was coming off of a wet and rainy winter and the ground was saturated. There had already been high waters in January and going into Good Friday (March 21), temperatures were around 70 degrees.

“An arctic cold front came down from Canada and the temperatures dropped from the 70s to the 20s in six hours,” she said. “High winds up to 90 miles an hour were reported in Toledo, and that alone caused a lot of damage, tearing down telegraph and telephone wires and poles.”

For the next four days, four different low pressure systems pinned the front down and created a trough diagonally across the country. The jet stream, unknown at the time, acted like a pump to draw moisture in from Caribbean to cover Ohio.

“The result was steady rain, over 11 inches in four days in some places,” Bell said. “No part of Ohio got fewer than four inches, but most of Ohio got eight inches or more.

“People talked about how fast the waters rose, sometimes one or two feet per hour, and there wasn’t any way of sending warnings down stream because of the downed wires,” she said. “There was no radio then except for a few ham radio operators, and the 1913 Flood is what triggered the legislation to create an emergency broadcast system.”

On March 25, the rising waters struck Hamilton and Middletown and the Great Miami River overflowed its banks. By 2:15 a.m. the next morning, all four of Hamilton’s bridges had washed away. Some 300 buildings were destroyed by the flood waters and another 2,000 had to be razed because of the damage that had been done.

In Middletown, six feet of flood waters wiped out pedestrian and railroad bridges and displaced more than 1,000 people. The banks of the city’s canal were so badly eroded by the flood that it basically spelled the end of the system, Ashworth said.

“It was just never feasible to rebuild,” he said. “There was some discussion to do it, even at the state level, but the cost was going to be prohibitive.”

The death toll in Hamilton has historically been estimated at around 200 souls, but was probably much greater than that. As part of the 100th anniversary commemoration, Kathy Creighton, executive director of the Butler County Historical Society, has been combing through records to create a data base of casualties, including those who died in the weeks and months later from the lingering health and safety effects.

Blount said that bodies turned up for months and years downstream, but because there was no DNA testing at the time — and no fingerprinting — it’s been difficult to get an accurate body count, but it could be as high or higher than 400.

“The death toll could have been much higher because the population then was only about one-fourth of what it is now,” Bell said, “and the same holds true for cost of the storm because people are much wealthier now.

“But within a couple of days it caused great damage as the rising waters moved across the nation and then hit cities down the Mississippi River, so it was really a rolling disaster until about May 1.”

A wake-up call

Certain community leaders in Dayton had been watching the recurrent floods for many years. There was a big one in 1805, 10 years after the city was founded, and another in 1866, according to Angela Manuszak, special projects coordinator for the Miami Conservancy District.

James Patterson, in fact, deliberately built the NCR campus on high ground and provided the factory with its own power plant and water infrastructure to forestall flooding events.

Within a year, the Ohio General Assembly passed the Conservancy Act of Ohio, which permitted the creation of regional agencies to provide flood protection for communities within the state.

Community leaders up and down the Great Miami Valley petitioned to form the Miami Conservancy District, which was established in 1915.

“Prior to the enabling legislation, most political decisions were made on a city-by-city basis, but water doesn’t recognize political lines,” Manuszak said. “The Conservancy board was designed to be apolitical, and their charge has been to look at flooding issues from a holistic basis, that they needed to solve the whole problem, not just one city’s problem.

Together they worked out a funding system and raised the bond money, about $35 million. Construction began in 1918 and was finished in 1922. It was the largest public works project of its day, but they put it on the fast track.

Manuszak said there were three main components to the Conservancy’s work in those years:

- Improved river channel by dredging, widening and in some places straightening out the river's course.

- Building levees upstream dry dams on four of the river's five tributaries, all of them protecting Hamilton and Middletown.

- Preserving the flood plain so that all land above the dams would remain green spaces with deed restrictions to prevent future construction.

To accomplish all of this, however, many roads and railroad lines had to be moved, Manuszak said.

“That all this was pretty incredible, not just because of the time frame but because most of the work was being done by hand,” she said. “But there were very few accidents among the 3,000 employees that worked on the project.”

Once the initial work was completed, the enabling legislation also allowed the Conservancy to do other water management things, including improving groundwater and surface water quality, to do projects to protect well fields, provide incentives to farmers to reduce nutrient runoff, build recreation facilities on the preserved land and the planting of hundreds of trees in the basin. The Civilian Conservation Corps kicked in to build shelter-houses, trails and picnic areas, a forerunner to the ongoing effort to build bike trails along the river that began in the mid-1970s.

Could it happen again?

Arthur Morgan, the chief engineer behind the flood protection project, wanted to know how to protect the river from ever being flooded again.

“To find out the volume of water, he sent a group of surveyors down the river with buckets of paint, asking people where the high water was and they would mark buildings,” Manuszak said. “They were known as Morgan’s Cowboys.

“They knew the record for stream heights in the U.S. were only a century old, but records in Europe went back 1,000 years, so he sent engineers there to search flood records,” she said. “They determined that the maximum flood of 1,000 years was about 25 percent more that what there were records for, so Morgan said that 40 percent would be unreachable.”

“We’re not even concerned,” Manuszak said. “We have not yet reached 25 percent of the capacity, and it would take at least twice the rainfall of 1913.”

Although Trudy E. Bell said that the region is largely safe because of the work of the Conservancy, a recurrence isn’t totally impossible.

The 1913 pattern of a slow-moving storm pattern of deep lows and blocking highs has occurred many times since and is “an absolute signal” there will be significant flooding somewhere around the Midwest.

With the work of the Conservancy, however, it would take twice as much rain, and people would be better warned and prepared than 100 years ago because of improved communication systems, so there would likely be a lower death toll, although runoff would be higher because of paved roads and parking lots so there would be more property damage.

Still, the Great Miami River is an integral part to the future of Hamilton, and is a major character in Hamilton’s master development plan.

City Manager Joshua Smith cites the existence of the Fitton Center for Creative Arts and the Courtyard by Marriott as good examples of the city embracing the river as a signature feature. The RiversEdge Amphitheatre is nearing completion of Phase I, and the first event there will be the final event of the flood commemoration.

The former Champion and Smart Papers plant, especially the riverside buildings, are going to be the focus of redevelopment in the near future, Smith said, and he expects there to be a big push toward more housing, particularly public housing, along the river.

“We have a great architecture visible on the river corridor,” Smith said. “It is definitely an assent.”

About the Author