According to a report sent to council by Tom Vanderhorst, the city’s executive director of external services, three of the properties are owned by Chem-Dyne Corporation, and three are owned by the state of Ohio.

The documents sent to council do not list prices expected to be paid by the city or the sizes of the parcels in the area of 500 Joe Nuxhall Blvd. But here are the parcels, and how large the website of Butler County Auditor Roger Reynolds says each is:

- Parcel P6431013000009, owned by the state for a forfeited land sale, 7.421 acres;

- Parcel P6431013000011, owned by the state, 9.204 acres;

- Parcel P6431013000012, owned by the state, 7.176 acres;

- Parcel P6431013000006, owned by Chem-Dyne Corp., 0.034 acres;

- Parcel P6431013000007, owned by Chem-Dyne, 3.035 acres; and

- Parcel P6431013000008, owned by Chem-Dye, 1.034 acres.

Benefits and risks

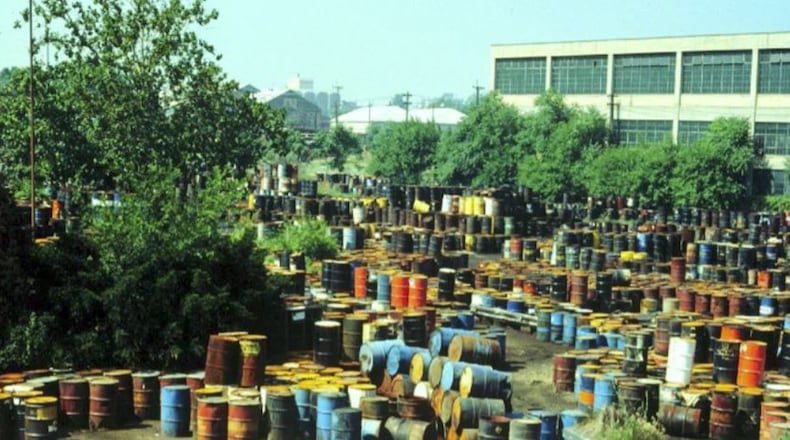

In a report to council, Vanderhorst wrote the Chem-Dyne Trust recently contacted the city about acquiring the former Chem-Dyne site parcels because the county auditor was advertising the land for a recent forfeited land sale. The city, aided by Butler County, delayed the scheduled forfeit sale to allow legal staff to work with state and federal environmental regulators to issue “comfort” letters on the properties.

Because it was a former Superfund site, city administrators “felt it was important to potentially acquire the site to preserve it. Staff would recommend proceeding with acquiring the former Chem-Dyne site from the current property owner(s) knowing the challenges associated with future development of the properties,” Vanderhorst wrote.

The city wanted to buy the land make sure someone else doesn’t buy it and do something irresponsible, City Manager Joshua Smith told the Journal-News in a December interview.

“This is more of keeping it out of someone else’s hands,” Smith said.

Andrew Kolesar, an environmental lawyer with the firm Thompson Hine, in December told council that despite the pollution — which the Chem-Dyne trust has worked to contain and clean by pumping polluted water from below ground at the site, cleansing it, and pumping back underground — Hamilton would have little liability by purchasing it.

The liability would be limited as long as Hamilton doesn’t use the land for disallowed purposes or disturb the cap on top of it, Kolesar said, adding that nearly all the liability belongs to the 100-plus organizations that are under a court decree to finance its cleanup and monitoring.

Also, those 100-plus companies remain responsible for the site’s pollution, “not the city,” Kolesar said.

Lack of transparency in property sales

Although state and local officials in recent years have touted transparency in government finances, property sales and purchases are one area where there is a major gap.

David Brown, a spokesperson for Butler County Auditor Roger Reynolds, has told the Journal-News there’s a reason sale amounts do not appear on county auditors’ property records that normally show transaction prices for everyone else. Under state law, the auditors are not allowed to post those prices when counties, cities or other local governments buy or sell land or buildings.

That was something Reynolds and others across the state have tried to change in recent years with various two-year sessions of the Ohio General Assembly, Brown said.

About the Author