“The city was shut down for a period of time. There was no tourism. There was no one riding the Metro. The Pentagon Metro station and bus station were closed,” Loewer said.

At the time she was a captain in the U.S. Navy. She had been in charge of the Situation Room for five months, and was also director of Systems and Technical Planning. She held those positions until June 2003, eventually retiring from the Navy as a rear admiral.

Loewer was traveling with President George W. Bush to Sarasota, Florida, on Sept. 11. She joined his motorcade to Emma E. Booker Elementary School. On the way she got a call from Senior Duty Officer Rob Hargis in the Situation Room, telling her a plane had hit the north tower of the World Trade Center. When the motorcade stopped she briefed Bush and Chief of Staff Andrew Card, but initial details were sketchy.

Credit: ERIC DRAPER

Credit: ERIC DRAPER

At the school, Loewer asked for a TV in the room next to the one where Bush was reading to children. That’s where she watched the second plane hit the other World Trade Center tower, making it clear this was no accident.

As the day went on, she learned the crash of American Airlines flight 77 into the Pentagon not only destroyed her office there, but killed 17 of her friends. A total of 125 people in the building died, along with 59 passengers and crew on the plane.

The ensuing weeks saw the pace of Loewer’s job quadruple, as National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice urged her to find and forward every scrap of relevant information.

“The level of intensity was significant for six to eight weeks,” Loewer said. “I can tell you that obviously 9/11 started a very focused and intense effort in planning the invasion of Afghanistan, and of gathering intelligence from theater and from various other sources, bringing that information into the White House. The mission of the Situation Room, 24/7, 365, is to put together a report twice a day for the president regarding any threats to our national security.”

Loewer has extensive notes from those days, but the events of Sept. 11 are so personal that she hasn’t looked for other accounts.

“I have not read any books from any author on the events of 9/11,” Loewer said. “Everybody has their own personal story from 9/11. I don’t intend to read more about that. I turn off the media on Sept. 10 every year and I do a time-out until Sept 12.”

A lifetime of preparation

Loewer’s career has been a string of firsts. As a teenager she was the first female cadet commander of Ohio’s Civil Air Patrol. Loewer was a 1972 graduate of Shawnee High School and went on to Wright State University, where she earned degrees in theoretical mathematics and computer science.

She joined the Navy out of college, planning to do a four-year stint and return to Springfield to teach. Instead, the Navy turned into a 31-year career.

Loewer attended a Surface Warfare Officer Basic Course in 1979 and graduated first in her class. She was then assigned to the USS Yosemite as an electrical division officer, operations officer, navigator and administration officer. Named an Olmstead scholar in 1984, she attended the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, and the Goethe Institute in Stuttgart, Germany. She earned her doctorate in 1986, and attended the Surface Warfare Officer Department Head Course and again graduated first in her class.

Credit: Bill Lackey

Credit: Bill Lackey

Loewer was the first woman to qualify as a Surface Warfare Officer on the East Coast. From 1993 to 1995 she commanded the ammunition ship USS Mount Baker, and the combat support ship USS Camden from 1998 to 2000.

She also spent 3½ years working for the deputy secretary of defense and the secretary of defense. That experience was one reason Loewer was tapped as the first woman to be Situation Room director and Systems and Technical Planning director at the same time.

After 26 months in the White House, she became vice commander of the Military Sealift Command. Following that she commanded the Navy’s Mine Warfare Command, the position from which she retired in 2007.

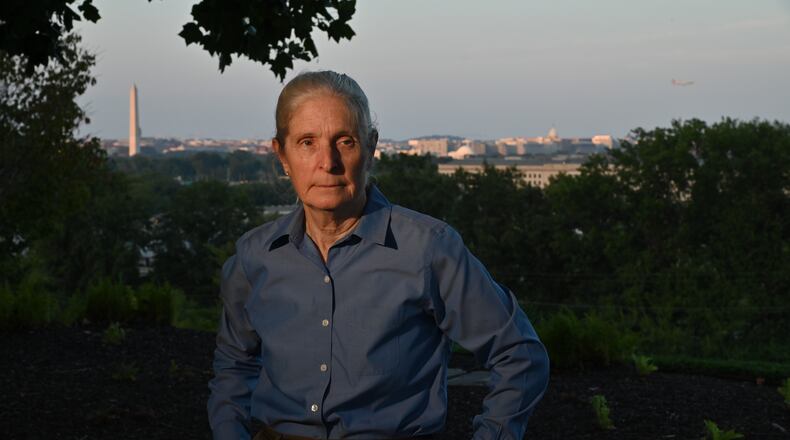

Next, Loewer worked for two years as vice president for homeland security at a small private company in the underwater acoustics sector. Then she returned to government, serving as a senior adviser to the under secretary for intelligence at the Department of Homeland Security. In 2013 she retired again. Since then she has been a volunteer advocate for senior citizens in Arlington, Virginia. She spends most of her time in the Washington, D.C. area.

“I do venture back to Springfield now and then,” usually to visit family, she said.

Aftermath – then and now

The Sept. 11 terrorist attack and the ensuing U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 were seminal moments in American history, Loewer said. For her, those days meant working at “lightning speed” to help track down al Qaeda members and anyone with any connection to the attack. But it also created closeness with colleagues and solidarity among Americans that lasted for months, she said.

“People who I interacted with right after 9/11 and for months afterward, we developed a sense of community and caring,” Loewer said. “And it was remarkable that people who didn’t know their next-door neighbor now knew their next-door neighbor, and wanted to check on them and make sure they were OK.

“That lasted for months, that feeling of taking care of people you don’t know. It didn’t matter what walk of life you came from. People were extremely kind.”

Now, as America exits Afghanistan after 20 years, Loewer says critical analysis and understanding of mistakes — political, military, diplomatic, economic and cultural — offer “a most reasonable pathway toward a better future for our country.”

She wasn’t involved in the drawdown of troops, which began under President Donald Trump, or the final withdrawal under President Joe Biden, which saw the collapse of the Afghan government and the Taliban’s return to power. Without that knowledge she can’t assess those actions, and cautions others against the same.

“It’s easy to criticize. I try to be very careful on my comments regarding what our administration, the Department of Defense, what NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) do,” Loewer said. “I found in my time as a commander that there are so many things you don’t know. It’s easy to sit back and say, ‘Why didn’t they do this?’ or ‘Why didn’t they do that?’”

Instead, people should be glad so many groups cooperated to evacuate Americans and Afghan allies, she said.

“The important thing is not to know all of the special things that happened to get them out, it’s to get those folks out,” Loewer said.

Learning from the past

Loewer has been asked many times to publish her career reminiscences, and she has plenty of material from detailed notes she took following major events. All she’ll say at this point is, “We’ll see,” but she does reflect on some lessons.

“As people look back on 9/11 20 years later, we can be very heartened by the fact that there were such dedicated Americans and foreigners that day who did so many things to protect our country,” Loewer said.

She cited passengers of United Airlines flight 93, who overcame al Qaeda hijackers apparently heading for the U.S. Capitol, and crashed the plane in rural Pennsylvania, killing all aboard; first responders in New York City who worked for months at the World Trade Center site; and Pentagon workers who never came home, or stayed to help others escape from the building.

“Remarkable is just not a good enough term for what those people did,” Loewer said. “I would like to think that many of us, our friends and neighbors, if they needed help like then, that neighbors would step up to help. That’s what Americans do. That’s who we are.”

Credit: charles caperton

Credit: charles caperton

Loewer would not comment in detail on the current state of the nation, as displayed by an angry mob’s attempt to stop Congressional certification of the 2020 presidential election. But she said friends and colleagues around the world shared her sense of tragedy.

“The storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, should be regarded as one of the most tragic days in U.S. history,” she said.

Several years ago Loewer spoke to a graduating class at her alma mater, Shawnee High School, to students who were 4 or 5 years old in 2001. What she told them is still the lesson she took from the tension of that day: “Don’t take life for granted.”

Loewer told the class each day is unknown, so they should think carefully about whatever they do and do it well.

“Life can be precarious but it’s also precious,” she said. “I would add that it’s not just life, it’s what you do: how you sacrifice to take care of your family, to take care of your neighbors. It’s how you behave.”

About the Author