The Greater Ohio Policy Center — a nonprofit that promotes urban revitalization — previously has estimated the real number of Ohio brownfields might be about 9,000.

Now legislation seeks to help the state’s local governments identify the brownfields within their jurisdictions, preparatory work needed to seek some of the $350 million Ohio’s current budget includes for brownfield cleanup.

“Redeveloping brownfield sites helps our region expand the inventory of viable industrial sites,” said Shannon Joyce Neal, vice president of strategic communications for the Dayton Development Coalition. “We have many examples of brownfield redevelopment, from industrial reuse such as Fuyao, to new research facilities like GE’s EPISCenter and Emerson’s Helix, to unique office environments like Tech Town. We welcome additional tools to support this work and make these sites ready for development.”

What’s a brownfield?

Brownfields are abandoned or underused properties, often old industrial sites, where possible lingering contamination hinders redevelopment. Identifying brownfields and knowing what sort of contamination is in the dirt, water and air are vital preliminary steps toward reuse of the land, according to Abinash Agrawal, professor of earth and environmental sciences at Wright State University.

Every brownfield site must undergo characterization, which means defining the contamination’s nature, location and extent, Agrawal said.

Contaminants can persist in soil, groundwater and even in the air as plumes of vapor, he said.

“Those things, if they have not been done already, need to be done before you can do clean up,” he said.

Brownfields exist in all of Ohio’s 88 counties, and the numbers are constantly changing, said Aaron Clapper, senior manager of outreach and projects at Greater Ohio Policy Center. Some sites are cleaned up and redeveloped, while elsewhere more businesses shut down and leave pollution behind, he said.

The Ohio EPA previously identified more than 2,500 brownfields in the state, sites both large and small with varying types and levels of contamination, Agrawal said.

Agrawal, who has taught remediation — that’s cleanup — of contaminated sites for 26 years, said his definition of brownfields doesn’t include former gas stations or dry cleaners, just industrial sites. Other definitions of brownfields include gas stations, dry cleaners and similar small businesses due to the chemicals they used and stored; but Agrawal said those can be taken care of more easily, such as by removing gas stations’ underground storage tanks.

The Greater Ohio Policy Center’s estimate of 9,000 brownfields includes small sites like former gas stations and dry cleaners, said Jason Warner, the group’s director of strategic engagement.

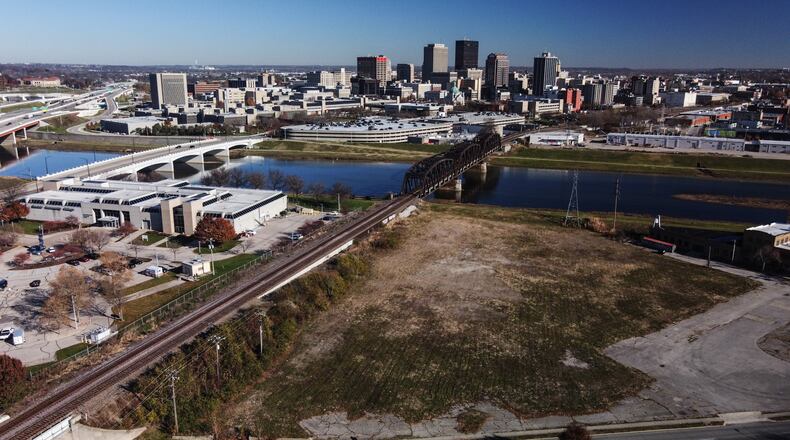

Agrawal said he is aware of several dozen brownfields in the Dayton area, including several large ones contaminated with industrial solvents.

“Some of those sites develop into Superfund sites,” he said.

Superfund sites are major hazardous waste sites identified under the federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980. The Superfund list, which includes 53 sites in Ohio, is managed by the U.S. EPA.

The intent of CERCLA was to get those responsible for the contamination to clean them up. But in recent years, cleanups have slowed as taxpayers shouldered most of the costs.

The Dayton region includes 19 Superfund sites, all separate from the state’s brownfield database.

What’s the proposal?

State Sens. Sandra Williams, D-Cleveland, and Michael Rulli, R-Salem, introduced Senate Bill 83 in February. It passed the Senate 32-0 in May. Now it’s in the House Agriculture & Conservation Committee, where it had a fourth hearing Nov. 17.

Initially the bill would have set side $150,000 for the Ohio EPA to conduct a study in conjunction with Ohio public universities to identify brownfields statewide and estimate their cleanup cost.

But on Nov. 17 the sponsors amended the bill to put that money instead into the existing Targeted Brownfields Assessment program.

“The cost of a statewide study of all brownfields, including potential sampling, would far exceed the current appropriation,” bill sponsors wrote.

Under the amendment, the money would go to pay for more targeted assessments of brownfields at no cost to local governments, said Kayla Lewis, senior legislative aide for Williams. Governments could apply for the money as grant funding.

The Ohio EPA would conduct basic investigations of known and previously unknown sites as a first step toward cleanup, Lewis said.

“A lot of times local governments have to do initial, first assessments, and this would help them do that,” she said.

The Ohio EPA gets about $427,000 per year from the federal government to do Phase I assessments of brownfields, which include interviews, visual inspection, record searches and identification of areas to sample for contamination.

Those normally cost $5,500 to $8,000, so the extra money would allow 18 to 28 more assessments in the coming year, the bill’s sponsors said.

Phase II assessments include sampling material from a site to determine what contaminants are present and at what levels.

The state’s Targeted Brownfield Assessment program pays for Phase I and II site assessments, allowing them to be done at no cost to local governments.

The bill as amended would focus the funding on Phase 1 site assessments, which would be carried out by environmental consultants, said James Lee, Ohio EPA media relations manager.

Funds allocated to the Targeted Brownfield Assessment program cannot be used for cleanup, Lee said.

Warner previously testified in support of SB 83, and hopes to reiterate that support for its new form. The amendment will help communities move closer to accessing cleanup funds, he said.

“We’re just as excited for that as we are with the creation of the brownfield remediation fund,” Warner said.

What’s the urgency?

Local government demands for site assessments are rising due to the impending availability of cleanup funds, Lewis said.

The state budget passed in June included $350 million for a new Brownfield Remediation Program through the Ohio Department of Development. Every county will get at least $1 million, with the remaining $262 million available as first-come, first-serve grants over the next two years. The state funding can pay up to 75% of a cleanup project’s cost, but has to be used within a year.

The budget also included $2.5 million for the existing Brownfields Revolving Loan Program, which provides low-interest loans to public and private entities for demolition, cleanup and remediation.

The state has lacked dedicated funding for brownfield cleanup since the 2013 end of Clean Ohio Brownfield Revitalization grants.

Currently, state and federal brownfield inventories rely primarily on voluntary reporting through programs such as the Voluntary Action Program and the Clean Ohio Fund. The state has not maintained a mandatory list of brownfields since the early 2000s, when it was successfully challenged in court, Lee said.

The state’s voluntary reporting database includes nine sites in Butler County; three each in Champaign, Clark and Greene; two in Miami, 16 sites in Montgomery County and none in Warren County.

Voluntary Action Program

There is no requirement that owners of brownfields in Ohio notify the state. Warner told legislators in June that a property owner must disclose its brownfield status only in the case of a sale.

Under the Voluntary Action Program, companies and property owners can investigate possible environmental contamination on their property and clean it up if necessary, in return for a state promise not to sue and assurance that no more cleanup is needed.

Sites that go through the state’s Voluntary Action Program are cleaned up sufficiently for their intended reuse, which may include commercial, recreational or residential purposes, Lee said.

Identifying brownfields and doing a thorough on-site assessment to understand the extent of contamination will be a long-term project, but an essential one before seeking money for remediation, Agrawal said.

University researchers can help the state by using techniques developed in the last decade to analyze and treat sites, and recommending cost-effective cleanup methods, he said.

The Dayton Development Coalition maintains an online inventory of more than 500 potential development or reuse sites throughout the region, used to attract new businesses.

The nonprofit agency uses programs offered through JobsOhio to assist with site development, Neal said. That includes JobsOhio’s revitalization loan and grant fund, which gives priority to locations where remediation costs are more than the value of the land. Typical grants are up to $1 million and loans range from $500,000 to $5 million, according to the JobsOhio website.

BY THE NUMBERS

307: Sites identified as brownfields in a voluntary Ohio EPA database

36: Sites identified as brownfields in Miami Valley counties in a voluntary Ohio EPA database

9,000: Estimate of how many former industrial sites with possible contamination might exist statewide

$350 million: Available in a new Brownfield Remediation Program from the state

$1 million: Available for each county through the Brownfield Remediation Program from the state

$262 million: Available as first-come, first-serve grants over the next two years through the Brownfield Remediation Program from the state

75%: Share of a cleanup project’s cost the Brownfield Remediation Program will pay for

Unmatched Coverage

The Dayton Daily News digs into the most important issues facing our community, including recent stories on what the new federal infrastructure bill will mean for Ohio and what is being done to combat high levels of veteran suicides. No other local media provides the in-depth reporting and context to help you understand what’s really going on.

About the Author