On Thursday, federal prosecutors in San Francisco announced that a federal grand jury in that city returned a 39-count indictment charging Brockman with tax evasion, wire fraud, money laundering, and other alleged offenses.

“As alleged, Mr. Brockman is responsible for carrying out an approximately two billion dollar tax evasion scheme,” Jim Lee, chief of IRS Criminal Investigation, said in a press release Thursday. “IRS Criminal Investigation aggressively pursues tax cheats domestically and abroad. No scheme is too complex or sophisticated for our investigators. Those hiding income or assets offshore are encouraged to come forward and voluntarily disclose their holdings.”

In the indictment, Reynolds is named several times. Prosecutors have painted a portrait of Brockman pushing false information about the company and using it as a vehicle for his alleged crimes, but the company itself is not named as a defendant.

Messages seeking comment were left with the U.S. attorney’s office in San Francisco.

A Reynolds spokeswoman told the Dayton Daily News Thursday that its business will continue.

“The allegations made by the Department of Justice focus on activities Robert Brockman engaged in outside of his professional responsibilities with Reynolds & Reynolds,” said a statement from a spokesperson for Reynolds and Reynolds. “The company is not alleged to have engaged in any wrongdoing, and we are confident in the integrity and strength of our business.”

“Mr. Brockman has pled not guilty, and we look forward to defending him against these charges,” Brockman’s attorney, Kathryn Keneally, in an email to newspapers.

Questions were sent to Reynolds spokespeople Friday about what provisions Reynolds & Reynolds might make for its corporate leadership as Brockman fights the federal charges.

A company spokesperson Friday said Brockman is working with his private legal counsel, and while the situation is evolving, he will continue to serve as CEO of Reynolds & Reynolds.

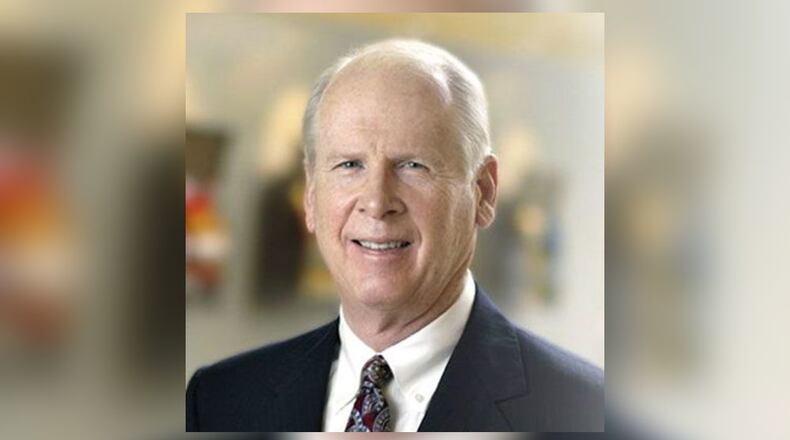

Brockman, a resident of Texas and Colorado, might be seen as an aggressive, successful businessman who makes bold moves.

In 2006, the then-65-year-old entrepreneur ran Universal Computer Systems, a Houston company he started in his living room more than three decades before, when he took over a much larger competitor, Dayton-based Reynolds and Reynolds Co., in a $2.8 billion deal.

In the indictment, prosecutors said a Brockman subsidiary, Dealer Computer Services Inc., borrowed $2.4 billion to finance the merger of Universal Computer Systems and Reynolds, paving the way to his ownership of the local company.

Both of Brockman’s companies then served a total of almost 11,000 North American car dealerships, Reynolds said in documents with the Securities and Exchange Commission at the time.

The indictment further portrays Brockman as setting up a “complex network of offshore companies and trusts designed to conceal $2 billion in gains earned from investments” in private-equity funds. Money was wired to bank accounts in Bermuda and Switzerland owned by an entity controlled by Brockman, prosecutors say.

In 2010, Brockman sued to obtain the identity of an anonymous blogger, dubbed “Trooper," who was often critical of him and Reynolds. The blog had been discontinued by the time of the suit.

The Brockman Foundation offers these biographical tidbits: Brockman served in the Marine Corps Reserve and has worked for Ford and IBM. He founded Universal Computer Services Inc. in 1970, decades before buying Reynolds and Reynolds.

About the Author