House members were expected to override two other property tax reform vetoes but stopped short because they didn’t have the votes. DeWine vetoed adjusting the school district 20-mill floor calculation to include emergency, substitute and other levies and income taxes and giving county budget commissions the authority to “unilaterally” reduce a levy passed by voters if they determine the funding isn’t necessary.

DeWine used his power to veto pieces of the $60 billion biennium budget three weeks ago. One effect of DeWine’s 67 line-item vetoes was to erase nearly all of the property tax reforms the House and Senate approved in the new two-year spending plan.

He explained his line-item vetoes.

“I line-item vetoed several provisions related to property taxes, I felt these ideas were thoughtful but I also was concerned that imposing them now, all of them at once, on our local schools would create a huge, huge problem,” he said. “And none of them guaranteed what we would end up with.”

Monday’s singular vote didn’t seem to satisfy House leaders on either side of the aisle.

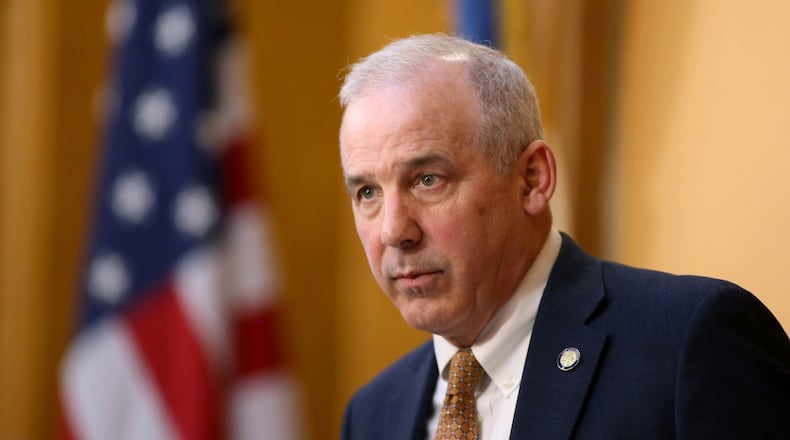

House Speaker Matt Huffman noted, however, that it was important to send a message “that this legislature is serious about doing something.”

He expects the House to consider further veto overrides in October following “more discussion.”

The Senate must concur before the override can take effect. Senate Finance Committee Chair Jerry Cirino, R-Kirtland, who co-chaired the conference committee that hammered out the budget differences between the two legislative chambers, said he isn’t sure when they might vote, but it will happen.

“I haven’t done a vote count myself, but the Senate majority with one exception voted for the budget bill that these components were a part of,” Cirino said. “I have not noticed any diminishment in people’s views on the validity of the property tax reform we originally passed.”

When asked why he pulled back from holding a vote on the other provisions, Huffman told reporters that some of his members had gotten cold feet.

“A couple of members called me this weekend. I frankly think they were getting bad information from locals about what those (provisions) would do,” Huffman told reporters.

Huffman described these provisions as incremental and noted that they don’t address the crux of the issue, which is that many Ohioans are seeing their property taxes rise at similar rates to their property’s value in a housing market where property values have soared in recent years.

“I would say these three provisions are largely in the line of transparency, clarity, and (they) give the opportunity for voters to know what they’re voting on and for locals to control taxes,” Huffman said. “Now, does it say like Proposition 13 did in California that you can only increase property taxes by 2% a year? No, but if you did have something like that that ties increases to (inflation), you wouldn’t have the 70% increase in Fairfield County.”

Huffman hinted that his sights are set on eventually capping yearly property tax increases in Ohio. “Those are the kind of reforms that have to happen. We have to get the increases under control.”

Democrats were unimpressed with Monday’s vote and noted that adding the provision back into the state budget will have no immediate impact on property taxpayers.

“This is not relief, and yet we use taxpayer resources to bring us all back to vote on what was ultimately political theater,” said House Minority Leader Dani Isaacsohn, D-Cincinnati.

Isaacsohn said the legislature shouldn’t override any of the governor’s vetoes on property tax, given that none of them, he argued, provide property tax relief. Instead, he backs enhanced homestead exemptions, a circuit breaker that gives state-paid income tax credits to offset property taxes for the needy and a commitment by the state to share more of its revenues with local governments to ensure that Ohio isn’t over reliant on property owners to fund local services.

Isaacsohn said he didn’t share Huffman’s interest in mimicking California’s Proposition 13 here in Ohio.

“I’m pretty committed to finding Ohio solutions for Ohio,” Isaacsohn said. “It’s a little rich that the speaker wants to look to California to get us out of this mess. The reality is, we’re in this mess because of the single party that’s been in power for decades in Ohio.”

Former Ashtabula County auditor Rep. David Thomas, who was hand-picked by Republican leadership to lead the way to property tax reform, told this news outlet the road to reform is obviously going to be rockier now.

“We will be still continuing our push with other bills and encouraging local governments to do the right thing in terms of tax rates,” he said. “But this really shows that we’re hampered with our current governor to do some big things. These were baseline, good reforms that didn’t actually slash local government but reformed the system in a good way for our voters. If we couldn’t get those over the governor we’ll have to see what else we can do.”

In his veto message DeWine announced the formation of a new working group — a joint legislative committee worked on it last year but produced no favored fixes — that has been tasked with recommending meaningful property tax reforms by Sept. 30.

Former legislators Bill Seitz and Pat Tiberi are co-chairing the group.