All three of the white whales, later determined to be of the Beluga species, were captured off the coast of Labrador at a point called “Dead Man’s End.”

The whales were transported to New York City by schooner, railcar and canal boat. From newspaper accounts of the time, it was reported that they were held at the New York Aquarium until purchased by Stewart for $10,000 and shipped to Cincinnati.

Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

The New York Aquarium, unlike today’s version of such establishments, was more of a circus act than a true scientific institution.

Given that whales were not a normal type of commodity shipped by rail, special arrangements had to be made. Railroad express companies, similar to what we now know today as FedEx or UPS, were solicited by Stewart to transport the whales. All but one, United States Express Company, refused to transport the creatures fearing they would not arrive alive.

The withdrawing express companies were correct. The first whale that was sent to Cincinnati died enroute in Cleveland on June 23, apparently for lack of water in his tank compounded by starvation. In this era, there was a paucity of information as to the humane handling and transportation of marine mammals.

The deceased whale, now packed in ice to prevent spoilage and resulting stench due to the heat of an Ohio summer, continued the journey to Cincinnati. Upon arrival, Stewart would donate the whale carcass to the Cuvier Club.

The Cuvier Club, named for Georges Cuvier, a renowned French naturalist and zoologist, was an organization dedicated to the enforcement of game and fishing laws in Ohio. The group established a free public museum of birds and fishes, and a reference library on these subjects at their location on Fourth Street in Cincinnati.

Professor Charles Dury, a taxidermist and custodian of the museum, had been tasked by the club membership to secure rare specimens whenever possible. Of course, nothing could be rarer than a dead whale in Cincinnati. Dury would undertake the effort to dissect and taxidermy the whale, stuffing its skin for the Cuvier Club.

Nonplussed, Stewart sent for a second whale, a 10-foot, four-inch female this time. The whale was loaded into a 14-foot box, this time made water tight, in Jersey City, NJ and sent via the Erie Railroad to Dayton.

In Dayton, the boxed whale was transferred to the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railroad passing through West Middletown, Hamilton and other communities on the line before being delivered to the CH&D Depot in Cincinnati on the morning of June 25, 1877. From the depot, the United States Express Company would load the boxed whale on a four-horse wagon and take her to the Lookout House.

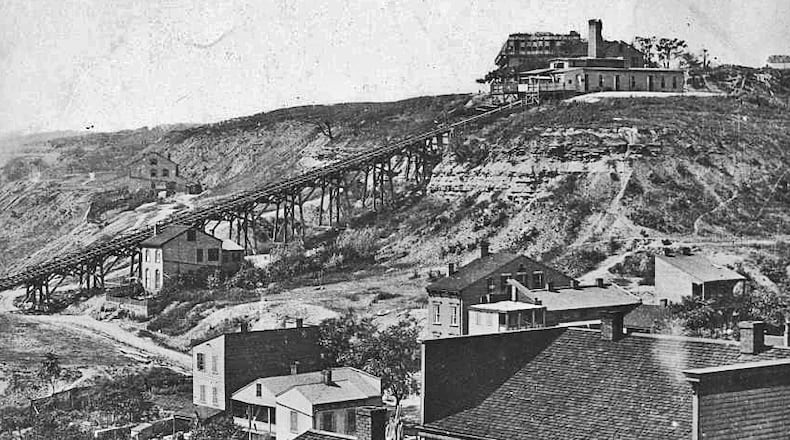

The Lookout House was located at Jackson Hill Park, high atop Mount Auburn and adjacent to the incline of the same name. Inclines of that time period were generally located near various destinations that offered entertainment, food and drink.

Such establishments would have various exhibits or features to entice incline customers to stay awhile and spend money. The Lookout House was legendary for openly flaunting Cincinnati regulations prohibiting the serving of alcohol on Sunday. The other allure of such venues, was that it was above the unwholesome air of the city, packed as it was with foundries, slaughterhouses, canals and other foul-smelling enterprises.

At the Lookout House, workman had previously erected an immense tank at the rear of the pavilion taking two days of round the clock effort to complete. The tank, which held 45,000 gallons of water, was 32 feet in diameter and eight feet deep. Around the tank was an amphitheater where visitors would stand.

As the box was transferred from the wagon, it took some 30 men to lift and tilt the contents, whale, seaweed and all into the tank. To add to this already bizarre scene, the Prussian Military Band, which performed regularly at the Lookout House, welcomed the aquatic visitor with the newly composed “Whale March.”

The new White Whale exhibit was open to the public at 7 p.m. that evening. Admission was 25 cents; 10 cents for children. Thousands of paying customers came to see this maritime marvel.

Unfortunately, this whale would live for only three days. Rumors would abound that it wasn’t a real whale, but a mechanical device. Other tales persisted that it had escaped its tank and was roaming the streets of Cincinnati. The cause of death, according to an autopsy, was injury to her head while being transported.

Given that her stomach was found empty, starvation was a more likely cause.

The third and final whale was dispatched from the New York Aquarium as a replacement and arrived on July 1 via the same train route. To remedy the starvation issue, George Taylor of Hamilton was contracted to supply some 5,000 minnows for the newly arrived whale to feast upon.

An advertisement in the Cincinnati newspapers the next day would implore readers to “See it Today, for Tomorrow it May be Dead.” It didn’t take long for that event to occur.

Alas, the third whale died on July 6. A fierce storm with high winds and copious lightning the night before apparently terrorized the whale, with witnesses stating that it had dived and thrashed about the tank as if possessed.

According to reports, the muddy Ohio River water, which had been pumped into the tank was stirred up by this frantic effort, coating the doomed creature and hastening its demise.

Ever the opportunistic showman, Stewart would arrange for the carcass of the third dead whale to be doused with carbolic acid as a preservative and displayed on a large, iced platform at the Lookout House, most likely with the intent of collecting an additional day or so of admissions.

So, with all the whales having deceased, what happened to their remains? The second was displayed at the Emery Building in Cincinnati and removed to a rendering factory on July 11, the stench being too great for further exhibition.

The third whale is presumed to have suffered the same fate after an icy public display at the Lookout House.

However, it would appear that the first whale, stuffed by Professor Dury would be sent to Hamilton on July 14. The Phoenix Restaurant and Billiard Hall, owned by Herman Reutti, and located within the Hamilton House Hotel at the northwest corner of High and Second Street would host the stuffed creature. The exhibit was to last for one week according to the Cincinnati Commercial newspaper.

Reports indicate that hundreds came to view the spectacle. Newspaper reports also indicate that this set of preserved remains ended up at the Cincinnati Natural History Museum, although officials contacted there can find no record of such a donation.

As for Albert Stewart, the owner of the doomed whales, he subsequently would go on to make his fortune in the advertising business and moved to New York City, becoming a part owner of the Barnum & Bailey Circus. Returning from a trip to Europe, his wife would arrange for him to take first class passage on the maiden voyage of the White Star liner Titanic.

Like his unfortunate whales, he would survive the journey for only a few days, before succumbing to the icy waters of the North Atlantic in the early hours of April 15, 1912.

Jim Krause is the author of the newly published book “Wreck of the Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton Railway – A Pioneering Railroad Undone by Greed and Fraud”, available for purchase at the Butler County Historical Society. He can be reached at jdkrause@fuse.net.

About the Author