But with President-elect Donald Trump and congressional Republicans vowing to repeal the 2010 law, Davidson, 43, of Canton, describes himself as being in limbo, saying “it’s hard to know what to prepare for because Republicans haven’t explained what repealing Obamacare would mean.”

“I’ll be in a big unknown,” he said.

Davidson is just one of millions of Americans who face the prospect of major revisions or complete loss of their health insurance when Trump becomes president. “If we don’t repeal and replace” the law “we will destroy America health care forever,” he said in Pennsylvania last week.

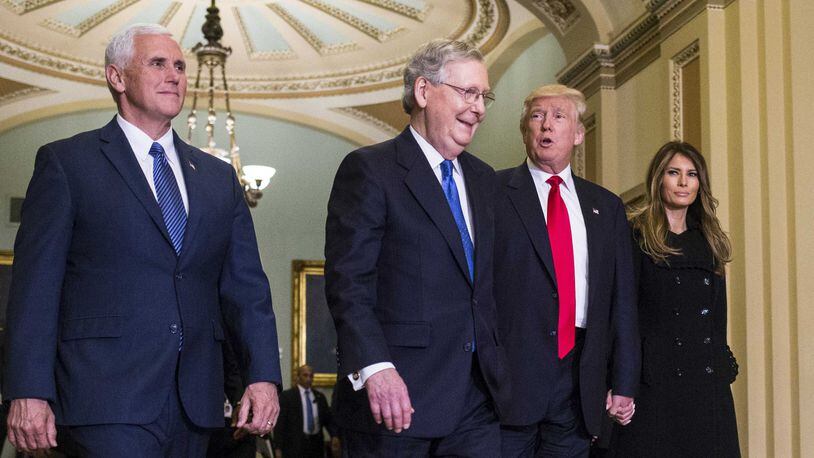

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., said scrapping most of the law is “pretty high on our agenda.” And after meeting Thursday with House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wis., Trump said, “We’re going to fix health care, make it more affordable and better.”

Yet while Republicans will have enough votes to kill sections of the law, the reality is they do not have a large enough majority in the Senate to undo the entire law and return to the health care system of 2008 before President Barack Obama took office.

“Even if the word ‘repeal’ of Obamacare remains the mantra for a while, the law is now sufficiently entrenched with six years of investment by the private sector that a total unwinding is unlikely,” former Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, R-Tenn., wrote last week in Forbes Magazine.

Tom Miller, a research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative non-profit organization in Washington, said “the idea of an early January robust repeal vote is not going to happen.”

But Miller said congressional Republicans “will have to deliver something that can be claimed to be a repeal — even if it’s not a 100 percent repeal — and signal toward what the replacement might be.”

Trump has yet to offer details on his own plan, leading some Republicans to suggest he would borrow from a more market-oriented proposal outlined by Ryan. But there is no certainty Republicans can find agreement on a new system, raising the possibility they could repeal the old law and fail to approve a new one.

“It’s the replace part that is the hardest,” said Peter Fenn, a Democratic consultant in Washington. “You have to have a plan. When suddenly 20 million people end up in emergency rooms, you will have a problem.”

Expanded role

President Barack Obama and congressional Democrats used their majorities in the House and Senate to push through the health law in 2010 despite the united opposition of Republicans, who argued it expanded the role of the federal government in the nation’s health care system, which comprises 18 percent of the nation’s economy.

Because 150 million Americans receive their health insurance through their employers, and 55 million seniors are covered through Medicare, the law was designed to cover roughly 20 million of the 47 million people without insurance in 2010.

The law provided federal dollars for middle-class people to buy private insurance policies through federal and state marketplaces known as exchanges. In addition, the law expanded Medicaid eligibility for low-income Americans by allowing a family of three earning $28,000 a year to qualify for the joint federal and state program.

The law prohibits insurance companies from denying coverage based on pre-existing health conditions and allows young adults up to age 26 to stay on their parents’ plans. Small companies were required to offer policies to their workers, and people without policies were mandated to buy plans or face a federal fine.

Although Davidson is not eligible for federal subsidies because he could receive insurance through his employer, he still qualified to buy a plan through the federal marketplace. The federal plan he hopes will be in effect in January costs $1,070 a month with a $750 deductible — much cheaper than his company’s plan, which charges $1,595 a month with a $1,500 deductible.

Premiums for plans bought through the state and federal marketplaces have soared in many parts of the country, in large part because younger and healthier people did not buy policies. A number of insurance companies dropped out of the marketplaces, which left people with fewer companies from which to choose their policies.

Ohio has one of the more competitive marketplaces in the country, with 11 companies offering plans for 2017. The U.S. Department of Health and Services estimates that more than half of the marketplace members in Ohio can purchase plans for less than $100 after the subsidies kick in.

Senate roadblocks

The House can repeal the entire law, but those favoring scrapping it run smack into Senate rules. While Senate Republicans can use a special parliamentary rule that would require only a simple majority of 51 senators to repeal certain parts of the law, such as the subsidies, Democrats can use a filibuster to block other changes.

“You’ll have all the insurance reforms staying in place, but all of the dollar pieces repealed,” said Kenneth Thorpe, a professor of health policy at Emory University in Atlanta and a former health care adviser in the administration of President Bill Clinton.

Yet those who know McConnell are convinced he will do his best to scrap the law. “I take Senator McConnell at his word and it’s going to be one of the first things out of the chute,” said Bob Stevenson, a former adviser to Frist and the late Sen. Warren Rudman, R-N.H.

Davidson can only wait and he’s not happy about it. “It’s been irresponsible to leave people hanging like that without some information about what (repealing it) would mean,” he said.

Jessica Wehrman of the Washington Bureau contributed to this story. Jessica Holbrook is a reporter for the Canton Repository.