But in what was becoming a recurring scenario over the past year, her husband Kevin was eagerly texting back and forth with his cousin Doug Spatz, who had been spending much of his free time in libraries from Dayton to Detroit, searching through microfiche back issues of newspapers.

And so those nightly exchanges between the O’Donnels and Spatz would go – according to the grinning Kevin and Doug the other day – something like this:

Doug: “You won’t believe what I just found!”

Kevin: “What?….What?”

Karen: “Hey, you guys got to stop it! Stop texting. Go to bed!”

Yet, from such passion – between Kevin and Doug, not Kevin and Karen – a Hall of Fame campaign has been born.

Their midnight mania has to do with their great uncle, Norb Sacksteder – “Hell on Cleats,” as the Detroit News referred to him in an October, 1916 article – who was one of the greatest stars in the early days of pro football.

• He was a team captain and the starting halfback for the Dayton Triangles in the first National Football League game ever played, an October 3, 1920, contest against the Columbus Panhandles at Dayton’s Triangle Park.

• He was the star halfback of the very first NFL champions, the 1922 Canton Bulldogs.

• Playing professionally in the five years that preceded the 1920 formation of the American Professional Football Association (APFA) – which would change its name to the NFL – Sacksteder was the game’s most dynamic presence: running the ball, passing, returning kicks and punts and playing defensive back.

At just 5-foot-9, 173 pounds, he was a small package who made a big impact.

As Spatz noted: “He changed the game from a rugby scrum type of contest to an open field game.”

He was like a jazz improvisation out there twisting, spinning, juking, changing direction, then cutting back again. Imagine an early-day Barry Sanders in a leather helmet and high top cleats.

Playing for the Triangles in 1916, he once scored seven touchdowns in one game.

In the early part of that 1922 championship season, he scored on a 60-yard punt return and a 38-yard run and threw a 35-yard TD pass.

In another game – against fabled Jim Thorpe and his Oorang Indians team – he had three interceptions.

Sacksteder would end up scoring more touchdowns than both Thorpe and the great and equally-inventive Fritz Pollard, both of whom have since been inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton.

And no one could attest to Sacksteder’s breakaway speed more than the legendary George Halas, who was playing for the Hammond Pros in that November, 1919 game against Sacksteder’s Detroit Heralds team.

Late in the game Sacksteder fielded a punt and returned it 60 yards for a score.

According to one Detroit newspaper account:

“Sacksteder’s dash was as pretty a piece of open field running as any fan would wish to see, for he had to elude men of such caliber as George Halas, Ghee, Blacklock, and numerous others whose ability to stop a runner is well known. Squirming, dodging and straight arming, the Detroit runner kept going at top speed until he struck the center-field bleachers with a crash that left him unconscious. He was picked up and rushed to the clubhouse, but an examination revealed no injuries.”

Halas – who’d later become the eternal cornerstone of the Chicago Bears – was not the only big name unable to corral Sacksteder.

As good in baseball as he was in football, Sacksteder was signed by the Philadelphia Athletics in 1916. When A’s manager Connie Mack told him to report in the fall, Sacksteder asked to delay his arrival until spring so he could play the football season with the Triangles. That ruffled the famed manager’s feathers and he wrote back that he “was not interested in pro football players.”

The season before, Knute Rockne had teamed with Sacksteder on the Massillon Tigers and over the years no one was paired more with Sacksteder than Thorpe. They were considered the game’s two best backs.

Before his pro days, Sacksteder was equally celebrated at the University of Dayton – then known as St Mary’s Institute – and also Christian Brothers College in St. Louis.

UD recognizes Sacksteder as a two-year football letterman and in the spring of 1913, he became the first Dayton Flyer ever – in a feat that’s been equaled just once since – to win letters in four different sports (football, basketball, baseball, track) in the same school year.

He played the 1914 season at Christian Brothers and by October, as one local newspaper there wrote, he had “developed into a football idol of St. Louis.”

And no wonder. His game against DePauw was highlighted in a Ripley’s Believe It or Not panel published in newspapers across the nation.

His feat?

He gained 506 yards in that game!

Yet all that fame came long ago and today few people – including the folks who vote old-time players in the Pro Football Hall of Fame – have heard of Sacksteder. So that’s where O’Donnel’s and Spatz’s passion now is directed.

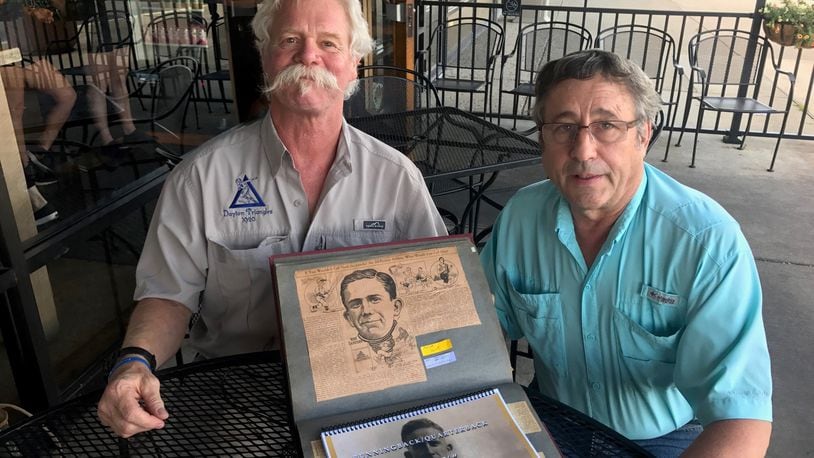

After a year of exhaustive research – Spatz in libraries, O’Donnel primarily dissecting every entry in Sacksteder’s treasure trove of a scrapbook – they have put together a comprehensive brochure filled with copies of newspaper clippings and book excepts on Sacksteder.

They are trying to get that to the nine members of the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee – which is part of the overall 48-member Selection Committee – and deals with players who have been out of the game a least 25 years and previously been overlooked or bypassed.

The cousins hope that Sacksteder – who they nominated for consideration next year – will become part of the expanded Centennial Hall of Fame Class of 2020.

For a long time players from those early years – especially those who starred before the APFA/NFL began in 1920 – have been mostly overlooked. But it’s the Pro Football Hall of Fame – not the NFL hall – and a guy like Sacksteder should not be penalized for when he played.

Still the two realize what they are up against.

“It’s a real longshot because no one knows who he is,” O’Donnel admitted.

Then again, the end zone was a long shot that day in 1914 when Sacksteder – playing for Christian Brothers – fielded a rival’s kickoff on his own goal line. As teammate Bob Gregor once told the late Dayton Daily News sports editor Si Burick, he played in that game and watched the return.

He said Sacksteder ran up the field, then back down and back up again, zig-zagging from one sideline to the other as wheezing defenders chased and grabbed, but never got more than a remnant of cloth.

According to Greger: “I’ll swear he ran 400 yards, at least…When he crossed the goal line, he was stark naked from the waist up except for his shoulder pads. The undershirt, sweat shirt and jersey had been ripped off.”

‘My god he is good’

While Spatz and O’Donnel said their grandmother was Sacksteder’s sister, they never met him.

They knew he grew up in East Dayton, went to high school at St. Mary’s Prep, played for the Dayton Cadets, who also would represent the University of Dayton and in 1916 help form the nucleus of the Dayton Triangles first team.

In 1960, after working various jobs in Dayton and Washington D.C., where, they said, he was an aide to a Congressman, Sacksteder moved to Florida. He and his wife, Martha, had no children and while older relatives went to visit him, he rarely came back here.

“We just heard he was a ‘good ball player,’” said Spatz, noting their family had several, including UD Hall of Famer Butch Zimmerman.

“And we heard he was cocky,” O’Donnell laughed.

When Sacksteder died in 1986 – at age 90 – his scrapbook went to the nephew named for him – Norb Zimmerman. Eventually, O’Donnell was given the book

After pouring through it and then reading Keith McClellan’s book – “The Sunday Game: At the Dawn of Professional Football” – O’Donnel told Spatz:, “My god he is good!”

The scrapbook included handwritten reflections by Sacksteder and one especially caught O’Donnel’s eye.

“Kevin was reading the scrapbook with his magnifying glass, which he always did, and saw where Sacksteder wrote he’d given a trophy he’d been given (by UD legend Harry Baujan for being one of Dayton’s greatest football players) to the Hall of Fame,” Spatz said.

“And right then it was like, ‘We gotta go there and find out what that trophy is about.’”

They did and Hall of Fame archivist Jon Kendle not only brought the trophy out of storage, but all the other material he had on Sacksteder, including clippings from that 1922 championship season.

Sacksteder dominated those headlines and that got the cousins even more enthused.

Although they both run their own businesses – O’Donnel lives in Miamisburg and is a professional wallpaper hanger with his O’Donnel & Company and Spatz lives Springboro and paints parking lots and roads with his Midwest Striping – they made Sacksteder a priority.

What O’Donnel said had begun simply as a venture “to verify for our family history”’ soon grew into the wondrous prospect that, as Spatz put it, “This guy could be in the Hall of Fame!”

Once they did all their research – they said they found clippings on every one of Sacksteder’s pro games – they took the next step. They found out who was on the Hall of Fame Selection Committee and decided the one person they might be able to get to was Geoff Hobson, the longtime Cincinnati sportswriter who is now the senior writer for Bengals.com.

He responded and wrote about their great uncle.

It was tougher reaching several of the Senior Committee members they said.

“We tried tweeting,” Spatz said with a laugh and a shrug. “We had never tweeted before. We tried to tweet five guys, but got no response.”

A few they wrote to did respond, including Rick Gosselin, the veteran Dallas Morning News columnist, who wrote about Sacksteder the other day on the State Your Case website.

O’Donnel and Spatz said the senior nominations gets pared down in August and the final vote will come the day before Super Bowl LIV next February in Miami.

They said every voter has preferred candidates – a couple of Cincinnati Bengal favorites are Kenny Anderson and Ken Riley – so they know they need to find someone to truly trumpet their case.

Or, as O’Donnel was told by Jack Carlson, the nonagenarian, fellow member of the Dayton Area Sports History (DASH) group:

“You need a rabbi!”

‘Bigger than life’

“We’ve been told we’ve got to find out everything he did,” O’Donnel said. “That we need to make him bigger than life.”

Although they haven’t delved much into Sacksteder’s life beyond football, they have some “bigger than life” threads to tug on.

“Our grandmother told a story how he helped people get to higher ground during the 1913 flood,” Spatz said. “And he did some security work and stopped a robbery where the guy had a gun.”

O’Donnel nodded: “And he was like a secretary for a Congressman. We have a little card that put him in the audience when FDR gave his speech (The Infamy Speech to the Joint Session of the U.S. Congress) on December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor.

“On the back he wrote, ‘This is when FDR wanted us to go to war.’”

“And he was at that Jack Dempsey-Tunney fight,” Spatz said.

“The long count one,” O’Donnel added.

And later in life, according to a 1966 Dayton Daily News story, Sacksteder served as a chaplain at the Bay Pines VA Medical Center near St. Petersburg.

Yet for all that, the place where he truly was bigger than life was on the football field. .

According to the pair’s research – regardless that newspaper accounts in Sacksteder’s day never included box scores and some statistics remain sketchy – Sacksteder played 61 pro games over nine seasons, scored at least 54 touchdowns, threw for a least eight touchdowns and had at least six interceptions.

Along the way he picked up a few other nicknames, including the “Ty Cobb of Football….The Dayton Dervish….The Phantom.”

The Cambridge Dictionary defines a phantom as “something that appears or seems to exist, but is not real or is imagined.” Additionally, it says “A phantom is also a ghost.”

And when it comes to the Hall of Fame, so is Sacksteder.

Saturday the Cincinnati Bengals held their first practice of the league’s centennial season at Welcome Stadium as a way to pay tribute to the Dayton Triangles and that first NFL game here.

And no one was a bigger part of that historic time than Sacksteder, so maybe this Bengals’ appearance will help make him and his Hall of Fame campaign more real, more visible to those who need to see it.

The hall of fame voters need the same vision Transylvania College coach William Steward had back in 1914 when his team faced the Sacksteder-led Christian Brothers team.

“This fellow Sacksteder is the best open field runner that I have ever seen and I have seen quite a few in my football experience,” Steward said in an October 28 article in the Dayton Journal. “He has a knack for shaking off tacklers that is remarkable and the way he uses a stiff arm makes him a player that any institution should be proud to claim.

“The youngster has a bright future. He has the speed, courage and all the other assets that tend to make a star gridder and, barring accident, he should carve his name in the hall of fame.”

If that happens, if Sacksteder’s likeness gets carved in bronze in Canton, then there will be no more midnight texts between Spatz and O’Donnel.

It will mean the Pro Football Hall of Fame voters had their eyes opened.

And it will mean that Spatz and O’Donnel can now shut theirs and dream sweet dreams.

About the Author