When all the votes are counted, Clinton may receive as many as two million more votes nationally than Trump. Yet for the second time in the last five elections, the candidate who won the popular vote was denied the presidency.

In U.S. history it has happened four times, and each time a Democrat was on the losing end in the Electoral College.

While the outcome of this election won’t change, the divisive presidential campaign has re-ignited an intense dispute over the future of the Electoral College, a process established by the founding fathers in 1789 that turns national elections in more than 50 mini-contests.

To critics, the Electoral College is a quaint relic that has gone the way of the musket, wooden sailing ships and voting restricted to white males.

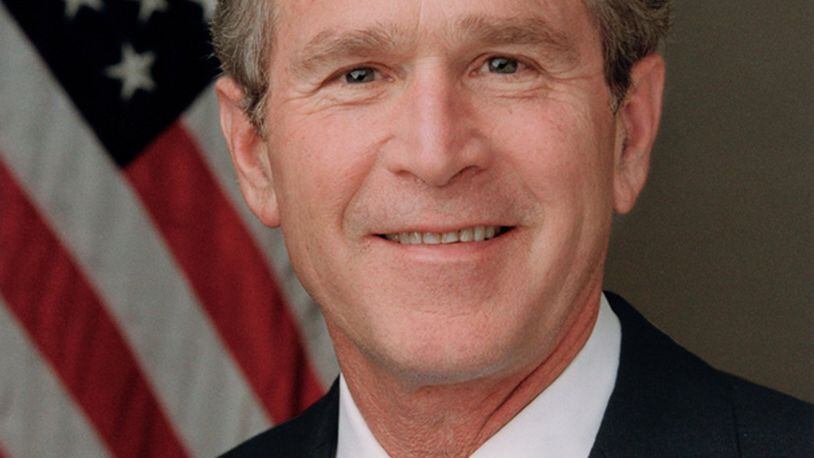

The 2000 and 2016 elections make the point, they say. In 2000, Democrat Al Gore won 543,816 more votes nationally than Republican George W. Bush, yet Bush prevailed with 271 electoral votes after the U.S. Supreme Court settled a dispute over ballots in Florida.

On Nov. 8, Trump had an even bigger Electoral College victory, pulling in 290 electoral votes.

“When we think of democracy, we think the person who won the most votes should win and that’s true for every other election” except president, said Alex Keyssar, a professor of history and social policy at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

“It doesn’t take a great exercise of imagination to think if it were reversed, Donald Trump would have launched the mother of all lawsuits,” said Keyssar, author of the soon-to-be-released book “Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?”

Some argue too that the apportionment of electors disproportionately benefits small states — which tend to be red states — because each state, no matter how small, is guaranteed three electors, one for each senator and representative.

But others, like Mike Dawson, creator of the web site Ohioelectionresults.com, say if the rules were changed, big states would “disproportionately decide who is president.’’

Abolishing the Electoral College would be “an invitation for chaos,” argues Ohio Secretary of State Jon Husted, a Republican. Without the Electoral College, candidates would devote most of their time to the largest states, such as California, New York, Texas, Florida, and Ohio, while ignoring smaller states such as Iowa and New Hampshire.

They point out if the national popular vote was close, such as John F. Kennedy’s 112,827-vote margin over Richard Nixon in 1960, it would prompt a protracted national recount that could last weeks before a winner was declared.

And they insist that without an Electoral College, there might be five or more presidential candidates instead of the two nominated by the Republicans and Democrats. In such a multi-candidate field, the winner could emerge with as little as one-third of the popular vote.

“Do you want California, which may not check an ID and allow anyone to vote…then have a more strict standard in Indiana where people check against those kinds of things?” Husted said. “We have the longest-functioning democracy in the world, and it has served us well.”

‘It was a fair election’

The framers settled on the Electoral College as a compromise between allowing Congress to pick the president or letting the voters decide. They opted for the states to pick electors — either through a popular vote or by the legislatures. The electors would then select the president.

The framers believed the Electoral College would lead to more nationally known and qualified people to become president. Originally, only a handful of states had voters select the electors, although by the 1830s most states held popular elections to choose electors. Today, electors are essentially bound to support the candidate who won their state.

Under the rules – long accepted by both parties – Trump emerged as the legitimate winner. “It was a fair election,” said Peter Ellis, 75, who lives in Beavercreek and voted for Trump. “It’s fair according to the rules. The rules are set up for those reasons.”

But critics say because Clinton won the popular vote by a healthy margin, it is difficult to conclude Trump earned a clear mandate from the American voters. If anything, more Americans voted for the status quo candidate than for Trump, who was promising sweeping changes in Washington.

“The only thing I say is our vote should count,” said Jackie Swenson, 56, a beauty supply store manager in South Charleston who voted for Clinton. “Every vote should count regardless.”

Those same critics say jettisoning the Electoral College would inject more enthusiasm among voters across the country. Only a handful of states, including Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Virginia, Florida, and North Carolina, are considered competitive and candidates spend most of their time in those states.

By contrast, a Democratic candidate can reliably count on winning California and New York while Republicans know they have major advantages in winning Texas and the deep South. As a result, there is no reason for any candidate to campaign in California.

“If you had a national popular vote, both parties would have a strong incentive to maximize their turnout,” Jack Rakove, a Pulitzer Prize winning professor of history and political science at Stanford University. “Everybody knows public opinion has been against the Electoral College for some time and this will reinforce that opinion.”

Abolishing the Electoral College, however, is extremely unlikely. It would require Congress to approve a constitutional amendment that would have to be sent to the states for their approval.

Changing demographics

Some argue that the country’s rapidly changing demographics may lead to more states being competitive, such as Texas.

“The Electoral College should move closer to the popular vote in time if we continue to be a more diverse country,” said Rep. Mike Curtin, D-Marble Cliff, co-author of the Ohio Politics Almanac. “That is more desirable than trying to change the U.S. Constitution.”

Jim Siegel of the Columbus Dispatch contributed to this story.